Mother of the Church

And thou shalt say in thy heart:

Who hath begotten these?

I was barren and brought not forth,

led away, and captive:

and who hath brought up these?

I was destitute and alone:

and these, where were they?

Isaiah 49, 21

GIVE praise, O thou barren, that bearest not:

sing forth praise, and make a joyful noise,

thou that didst not travail with child:

for many are the children of the desolate,

more than of her that hath a husband,

saith the Lord.

Isaiah 54, 1

When Jesus therefore had seen his mother

and the disciple standing whom he loved,

he saith to his mother: Woman, behold thy son. After that, he saith to the

disciple:

Behold thy mother. And from that hour, the disciple took her to his own.

John 19, 26-27

Of all the enigmatic statements in sacred Scripture, the one made by Jesus to his beloved disciple from the Cross is no less mysterious and challenging to interpret or understand. Our Lord says to the Disciple: “Behold your mother.” By the word mother, Jesus has more of a biblical sense in mind. His act of entrusting his mother to the disciple rests on the status and importance of motherhood in Israelite society. For the Jews, motherhood was more a social edifice than a biological expedient. Biblically, it was redefined as something that embraced all of God’s chosen people, given the historical circumstances surrounding their covenant with God and His promise to Abraham.

For instance, Ruth was enjoined by her mother-in-law Naomi to lay at the foot of the bed of her lord Boaz, who happened to be a relative of her deceased husband. Under the law of Moses, a close relation was expected to marry a widow to perpetuate the family name and keep all the assets, such as land, within the family (Deut 25:5-10). It was important that when a man died without having a son, a relative should marry a widow so that a son should be born within the family and its name carried on (Lk 20:27-40). Now, Ruth was childless when her husband died. But after she had married Boaz, the couple had a firstborn son whom they named Obed. The family name could now be carried on, and all the property kept within the family.

Thus, Ruth’s motherhood was not merely centered on giving birth to and nurturing children within the immediate family but was redefined in terms of a broader social scope that concerned the interests of the extended family and its preservation. Still, in Judaic religious thought, her motherhood extended even further by embracing all the children of Israel. Having given birth to Obed, Ruth did, in a sense, give birth to David. Her grandson Jesse begot the King of Israel. Providentially, Ruth’s motherhood extended to King David, from whose royal line the Messiah would come by being born of the Virgin Mary (2 Sam 7:12-13), whose dual maternity is prefigured in this Hebrew matriarch among others.

Leila Leah Bronner (Stories of Biblical Mothers: Maternal Power in the Hebrew Bible, University Press of America, 2004) has introduced the biblical concept that she coined “Metaphorical Mother.” This term refers to a woman who figuratively gives birth to and nurtures an entire population of children who are hers symbolically, if not also biologically. Ruth metaphorically gives birth to the people of Israel, who would be ruled by the Messiah by her biological ties with him through Obed, Jesse, and King David. Socially, she contributes to the birth and growth of a blossoming nation and the advancement of its people. Similarly, Sarah gives birth to Isaac, who in turn begets Jacob, who represents Israel. By giving birth to Isaac, she does, in a sense, give birth to the nation of Israel, and by doing so, her motherhood is redefined (Gen 12:2; 46:3). Yet Sarah’s maternity isn’t intended to be confined to national boundaries – not according to the Divine plan.

We see that all three of God’s promises to Abraham are fulfilled in their primary context in the Old Testament. In their secondary signification, they are fulfilled in the New Testament. All the families (nations) of the earth that shall be blessed together with the saved remnant of Israel as children (seed) of Abraham comprise the Gentiles who have been called to turn from their pagan iniquities now that Christ has risen from the dead, having reconciled mankind to God (Acts 3:24-26). Only those of faith (a steadfast love of God and trust in Him) are the genuine offspring of Abraham – both Jew and Gentile alike (Gal 3:7-9). There is “neither Jew nor Greek” among those who have been baptized in Christ and have “put on Christ” by conducting their lives in faithfulness to God’s commandments. All who are faithful to God, by walking in the light as our Lord is in the light, are children of Abraham, not only the Jews who have been circumcised (Gal 3: 26-29).

Thus, the primary fulfillment of God’s three promises to Abraham, including Sarah’s important maternal role, finds its secondary fulfillment in Jesus with his mother, Mary. Just as Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob prefigure Jesus and his Church, so does Sarah prefigure Mary, the Matriarch of the new and everlasting Covenant established through the precious blood of her divine Son.

That the first Jewish converts to the Christian faith perceived this link between the two women is evident by the parallel St. Luke draws between the birth of Isaac and the birth of Jesus. In Genesis 11, we have Sarah, the free wife of Abraham and mother of the promised son, whom she gives birth to miraculously, seeing she was barren and past the age of having children (Gen 17:17-18;18:10). It is by God’s command that he is to be called Isaac (Gen 17:19). As the free wife of Abraham, Sarah stands in opposition to her slave woman Hagar, one of Abraham’s concubines. Because Sarah is barren, she advises that Abraham and her servant Hagar have a son whom they named Ishmael. Still, Sarah later demands that he must never have a share in her son Isaac’s inheritance and should be sent away with his mother because of his foul behavior (Gen 21:8-10). Isaac is destined to become the father of a great nation, Israel in the person of his son Jacob.

In the Gospel of Luke, we have Mary, the mother of the promised Son, who is the rightful heir and Head of the kingdom of heaven. She is the free spouse of the Holy Spirit, through whom she has been endowed with a fullness of grace (Lk 1:28). The purity of her soul and freedom from all stains of sin magnifies the Lord (Lk 1:46). Together with the free Son of promise, she is at enmity with Satan and stands against all his offspring: sinful and wicked humanity (Gen 3:15). Mary is a virgin but, nevertheless, miraculously conceives and bears her only son Jesus (Lk 1:35). And not unlike Sarah, she questions how she could possibly conceive him, seeing that she does not have sexual relations with a man: “I know not man” (Lk 1:34). Yet, she is to conceive and bear a son who shall be called Jesus by God’s command (Lk 1:31). He shall rule all nations from the throne he inherits from his ancestor David, and his kingdom shall never end. As Isaac has begotten Israel, Jesus shall beget the Church and reign over Jacob’s descendants, his co-heirs, forever (Lk 1:32-33).

The Biblical theme of the free Woman of Promise occasionally appears in sacred Scripture from Genesis 3 to Revelation 12. God first chose Sarah to be a matriarch of the Israelites (the Matriarch of the Covenant) and not merely the biological mother of Isaac and maternal head of the extended family. She is called to participate actively in collaboration with God for the birth of a nation from which the Messiah will come to reconcile humanity to God. Other matriarchs of the Hebrews include the heroines who faithfully contribute to the salvation of God’s chosen people by collaborating with Him to liberate them from bondage and impending death at the hands of their enemy invaders or captors.

The three more highly acclaimed of these women in the Judaic tradition are Esther, Jael, and Judith. Along with Sarah, they prefigure the Virgin Mary in her redefined maternal role in the economy of salvation, whose valiant deeds find their ultimate fulfillment in Mary’s association with her divine Son in his redemptive work. Both Jael and Judith strike victorious blows for Israel by severing the heads of the chieftains of their enemies, Sisera and Holofernes, respectively, under God’s providential direction at appointed times, when God wills to restore His alienated people in His grace by the oath he had sworn to Abraham (Gen 22:15-18). And because of their saving acts in union with God, these valiant women are praised and proclaimed blessed (eulogeo) above all women together with Him, as all generations of the Jews shall follow suit (Jdgs 5:24-27; Jdt 13:18-20; 15:9-10).

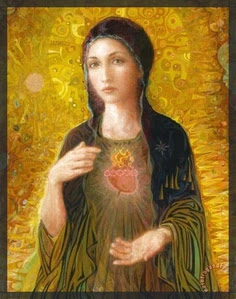

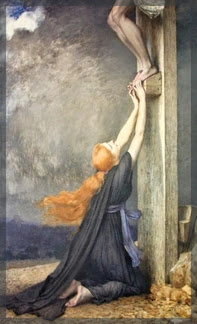

Mary crushes the head of the serpent, which is Satan, in collaboration with God when she humbly and faithfully consents to be the mother of the divine Messiah and suffers at the foot of the Cross in union with the afflictions of her Son to make temporal satisfaction to God for the sins of alienated humanity and help liberate it from the slavery of sin and the power of the hostile enemy (Lk 1:38; 2:35). By her Fiat, she brings the living Font of redemptive grace into the world, by whose merits all people shall be reconciled to God and restored to friendship with Him. Through Mary’s womb, God fulfills His third promise to Abraham of regenerating mankind in Christ and delivering all souls from eternal spiritual death and separation from the Beatific Vision of God. In commendation of Mary’s faith in charity and grace, Elizabeth pronounces her kinswoman blessed (eulogeo) above all women together with the fruit of her womb (Lk 1:42), and all generations of the Christian faithful shall as well because of the great things God has done for her in their collaboration together (Lk 1:48-49).

Esther is captured and enslaved with her people by King Ahasuerus (Xerxes), but because of her exceptional beauty, he chooses her from among all the Jewish maidens to be his wife and to reign with him as Queen of Persia (Est 2:1-18). She abhors the thought of being his wife, not only because he is an evil Gentile who has enslaved the Israelites, but also because she is a righteous woman who observes the Torah and is married to Mordechai, according to the Talmud. But the king forces her to be his wife and to lay with him whenever he summons her to his bed chamber. Meanwhile, all the Hebrew captives have been condemned to death through the schemes of an enemy, the king’s highest official, Haman the Agagite, except for Esther because of her marriage to the king. After her heartfelt prayer to God (Est C:12-30, NAB), and taking advantage of her singular privilege, Queen Esther manages to foil Haman’s plot, despite risking her own life, and saves her people from certain death. In his wrath, the king orders his highest official to be hanged by the neck on the gallows (Est 7:6-10).

Being Esther’s anti-type, Mary, alone of her race, isn’t subjected to the corruption of physical death and the dark prospect of eternal spiritual death because of original sin, brought about by the machinations of the Devil (Gen 3:14). God has exempted her from being born under the law of sin and death by preserving her free from the stain of original sin so that she shall be the worthiest of mothers for the Son and assist Him in defeating the world’s chief enemy Satan as to deliver mankind from its slavery to sin and impending death. Through the Fiat of the faithful and valiant daughter of God the Father, the King of kings claims the final victory over the chief enemy of God’s people and his works (Rom 8:37; 1 Cor 15:57; 2 Cor 2:14, etc.). Now in Heaven, Mary dons her crown and reigns enthroned as Queen together with our Lord and King, as the faithful continue to make war with the dragon in their spiritual battle against it together with her (Rev 12:17). Our Lady has been chosen by our Lord and King because she is the fairest woman of our human race (Lk 1:28, 42).

When Jesus addresses his sorrowful mother from the Cross, he calls her “Woman.” Jewish men of his time in Palestine honorably called their mothers Immah (Aramaic), especially in public observance of Mosaic law. However, Jesus refers to his mother, Mary, as a mother to someone when he says to the Disciple: “Behold your mother.” So, Jesus doesn’t think of Mary as his natural mother when he speaks to her and then to the Disciple, but rather as a mother to others in a spiritual sense. Our Lord is addressing his most blessed mother in a biblical sense. The truth is when Jesus calls his mother “Woman,” he is alluding to her as being the free Woman of Promise foretold to the serpent by God Himself in the Garden of Eden, she who shall crush its head by her faith working through love for the spiritual benefit of humanity (Gen 3:15; Lk 11:27-28).

Indeed, our Lord is affirming his mother to be in her person the culmination of all the Hebrew Matriarchs who have gone before her, beginning with Sarah and the promises God made to Abraham, of which his wife had a vital role to play in the economy of salvation in anticipation of the Incarnation. It is from the Cross, while his precious blood is being poured out for the remission of sin that Jesus declares his mother to be the Matriarch of the New and Everlasting Covenant and the spiritual mother or second Eve of redeemed humanity.

It is from the Cross, of all places, where our Lord redefines Mary’s motherhood, for through the Cross, she acts as the Mother of all Nations should by nourishing fallen humanity with the redemptive fruit of her womb – the body and blood of her divine Son, by which all souls may be reborn to a new life in the Spirit. As the caregiver of all human souls, Mary feeds and nourishes her spiritual offspring, the “true manna come down from heaven” and “the bread of life” (Jn 6:35, 51, 58), with the Cross standing ever-present before her. Mary’s maternal saving office isn’t only affirmed and ratified by Jesus as he speaks to his mother and the disciple from the Cross.

The Church was born in Calvary, so Mary’s saving office was established there until the end of this age. As Mother of the Church, Mary exercises her new maternal role by nourishing and strengthening all Christ’s disciples with the “Word for childhood” and the graces her Son has merited for them. The filial bond that Jesus forms between his mother and the disciple relates to his Messianic reign and all he has accomplished for humanity. His words to his mother Mary and the Disciple point towards his resurrection, ascension into heaven, and the descent of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost (Acts 2:1-4).

The couplet “Behold your son – Behold your mother” bears eschatological significance. So, when Jesus says to the Disciple, “Behold your mother,” he isn’t merely asking a friend to do him one last favor before he departs. Jesus does not primarily or exclusively mean that the Disciple should look after his mother once he is gone, though he does have her well-being in mind. This couplet's underlying force and structure dismiss the idea of such an ordinary or practical last will and testament. We mustn’t forget that every word (dabar) spoken by our Lord recorded in the Gospels carries soteriological weight, either explicitly or implicitly.

In any event, being aware of how people in his time were affected by the last words of a dying person or someone who foresaw his approaching death, John constructs this couplet in such a forceful and imperative way that does not smack of a simple request for a favor from a dear friend, but instead of Divine providence. He draws his readers’ attention to something of great soteriological and eschatological importance, which is to bear on the divine plan (economy) of salvation. Jesus certainly has the welfare of his mother at the back of his mind because of his perfect love for her and in honor of her. Still, he has chosen to place her in his disciple’s care from the Cross since it is from the Cross he wills to redefine her motherhood, given his mother’s final perseverance in faith and her vital role in the redemption, which required that she take up her cross together with her Son.

It is on Mount Moriah where God redefines Abraham’s fatherhood at the altar of the holocaust because of his obedient act of faith (Gen 22:16-18), and it is on this same mount, also called Golgotha, where God incarnate redefines Mary’s motherhood from the Cross because of her faith in charity and grace. Jesus has her moral participation in his redemptive work in mind. Mary’s spiritual motherhood of the redeemed has its raison d’etre in her co-redemptive role, beginning at the Annunciation.

The couplet “Woman, behold your son – Behold your mother” has a flavor of absoluteness. It is pronounced directly and borders on the imperative that essentially is a Divine decree. The first word (dabar) that Jesus utters while in agony for our sins is “Woman,” which immediately draws our attention to Mary, the mother of Jesus, at the foot of the Cross. The word redefines her motherhood and defines who she is in the Divine economy of salvation. The temporal circumstance Mary finds herself in as the mother of Jesus is the least of the Evangelist’s concerns. The author first draws our attention to the fact that she is the woman promised by God who will crush the head of the serpent by her faith in collaboration with God. Only then is our attention drawn to the Disciple to clarify what it is that Jesus means by calling his mother “Woman” instead of “Mother” (Immah), and how she relates to all the faithful in the order of grace. This device is known as constructive or synthetic parallelism in modern biblical exegesis.

Therefore, what is more significant than Mary being the mother of Jesus and having to be looked after once he is gone is her title, which denotes her new maternal and spiritual filial relationship with the Disciple. Now that Jesus has accomplished his mission and has cast the Accuser from heaven, Mary’s motherhood to Jesus recedes into the background. Mary does not assume the new role of being the mother of the Disciple after he takes her to his home (not that John needs an adopted mother in the ordinary sense), but she does at the foot of the Cross together with him standing there since it is because of the Cross that she becomes his mother, having had a painful intercessory role to play for the temporal remission of sin in her Son’s redemptive work.

Of all Christ’s disciples who had abandoned Jesus when he was betrayed and arrested in the Garden of Gethsemane, only John overcame his fear of being arrested. He mustered the moral courage to stand beneath the Cross with Mary, the mother of his Lord. The Disciple, therefore, becomes a spiritual offspring of the mother of Jesus, as she becomes his mother because of his faith. From the Cross, the Son designates his mother, Mary, to be the Mother of the faithful – her Son’s true disciples (Rev 12:17). Of the Eleven, only John accompanied the Mother of their Lord to the Cross. At the same time, the rest had given their Master up for dead, despite what he had already prophesied to them on their way to Jerusalem before his arrest (Mt 20:18; Mk 10:33; Lk 24:7). So, John’s presence beneath the Cross close to Mary is symbolic rather than purely incidental.

While the image of Eve provides a robust background for the redefinition of Mary’s motherhood, John also employs the Old Testament imagery of Mother Zion. And in doing so, he captures our attention to Mary and the Disciple with no name. The fact that he is present with Mary at the Cross indicates that he, too, has a role to assume, which God wills to reveal. This role is immeasurably more significant than that of a caretaker. Indeed, Jesus wishes to place his mother in no better hands, but he chooses to do so on this occasion to disclose something vitally essential to God’s plan of salvation. Thus, Mary is to be the caretaker of the Disciple’s soul as the pre-eminent moral channel of her Son’s grace to aid him (and all his associates) in his apostolic ministry.

The more reasonable explanation of the Disciple’s presence must be that he represents the entire Christian community of believers or the Mystical Body of Christ. Such an idea rests on a biblical mindset that scholars call “corporate personality,” which originated from biblical scholar H Wheeler Robinson (Corporate Personality in Ancient Israel, Edinburgh: T&T Clark Publishers, 1993). The beloved disciple is a corporate representation of the Church, which shall include even the Gentiles, just as Jacob is a corporate representation of all the faithful people of Israel who prefigure the faithful citizens of the New Jerusalem to come down from heaven (Rev 12:1; 21:2). In the biblical sense of motherhood, then, the Disciple is as much a son of Mary as Jacob is a son of Sarah, the mother of Isaac who prefigures Christ, and the Israelites the sons and daughters of Mother Zion – the second Eve in classical Jewish theology. Yet, for the early Hebrew Christians, the mother of their Lord wasn’t their spiritual mother in a simply metaphorical sense. She was someone whom they could personally relate to as much as they could her divine Son. Mary was much more to them than a symbol or representation (Lk 1:43).

For I heard a cry as of a woman in

labor,

anguish as of one bringing forth her first child,

the cry of daughter Zion gasping for breath,

stretching out her hands,

“Woe is me! I am fainting before killers!”

Jeremiah 4, 31

The sorrowful scene at the Cross is Old Testament imagery and symbolism related to prophecy and the Judaic traditions. Isa 49:21, 54:1-3. and 66:7-11 carry the theme of Mother Zion amid sorrow over the loss of her children when suddenly she is given a new and large family restored in God’s grace, which is cause for rejoicing (Lk 1:46-49; Zeph 3:14-17). In the words of Raymond E. Brown: “The sorrowful scene at the foot of the Cross represents the birth pangs by which the Spirit of salvation is brought forth (Isa 26:17-18) and handed over (Jn 29:30). In becoming the mother of the beloved disciple (The Christian), Mary is symbolically evocative of Lady Zion who, after birth pangs (interior agony or sorrow) brings forth a new people in joy” (The Gospel According to John, Garden City: Double Day & Co., 1966). Indeed, in the figure of Daughter Zion, Mary can compare her former desolation beneath the Cross with the bustling activity of returnees from exile filling her towns and cities. The returnees from the Babylonian exile foreshadow all believers in Christ who have been freed from the bondage of sin and impending eternal death.

Paul D. Hanson adds: “Zion is not destined to grieve because of the loss she has endured, viz., the death of her Son. Instead, she will be able to compare her former desolation with the bustling activity of returnees (from exile) filling her towns and cities” (Isaiah 40-66: A Bible Commentary, Westminster John Knox Press, 1995). According to the author, the three-fold references to the children represent repopulated Zion. The returnees from exile foreshadow all believers in Christ who have been freed from the bondage of sin and impending eternal death, having been ransomed by the precious blood of Christ, but at the reparative cost of his blessed mother’s sorrow and anguish beneath the Cross (Rev 12:4).

Enlarge the place of thy tent,

and stretch out the skins of thy tabernacles,

spare not: lengthen thy cords,

and strengthen thy stakes.

For thou shalt pass on to the right hand, and to the left:

and thy seed shall inherit the Gentiles,

and shall inhabit the desolate cities.

Isaiah 54, 2-3

The demonstrative particle “Behold” (Gk. Idou, Heb. Hinneh) is sometimes used as a predicator of existence, something that looks to a new state of being (the redefinition of Mary’s motherhood). The hinneh clauses emphasize the immediacy of the situation (the crucifixion) and may be used to clarify things. For instance, “Behold (here is) Bilhah, my servant. Sleep with her so that she can bear children for me and that I too can have a family by her” (Gen 30:3). Significantly, most hinneh clauses occur in direct speech. They introduce a fact or something actual on which a subsequent statement or command is based and must be closely observed. What Jesus says to the Disciple is, “Here is your mother,” meaning she is as much of a mother to him as Bilhah is a servant of Rachel – and Mary, the handmaid of the Lord: “Behold, I am (here is) the handmaid of the Lord” (Lk 1:38).

Thus, Mary did not become John’s mother figuratively, as in being like a mother of his by living under the same roof with him and managing the household. She became his genuine mother, along with all Christ’s other disciples, but in a spiritual and mystical sense. Mary became as much the mother of John and all her Son’s disciples as she did God’s handmaid and spouse of the Holy Spirit by the will of God.

Your sun will never set again,

and your moon will wane no more;

the LORD will be your everlasting light,

and your days of sorrow will end.

Then all your people will be righteous

and they will possess the land forever.

They are the shoot I have planted,

the work of my hands,

for the display of my splendor.

Isaiah 60, 20-21

Finally, we have the statement “Behold your mother” occurring in Matthew 12:47 and Mark 3:32. The theological theme in these two verses resembles that which we have in John 19:25-27. Both deal with what it means to be a “brethren of Jesus.” The crux of these passages is that the ties of obedience to the will of God take precedence over those of blood kinship. Although Jesus does not deny or intend to belittle his kinship with his mother, he nonetheless subordinates it to a higher bond of kinship that transcends all biological ties. Jesus regards Mary as his genuine mother more for her faith in God than their physiological ties since it is a more tremendous blessing to her (Lk 11:27-28). Our Lord tacitly has the Annunciation and Crucifixion in mind when he answers the crowd after his attention is drawn to the presence of his mother and kin outside. They represent the extension of boundaries and point to the inclusion of the Gentiles in the New Dispensation of grace. Our heavenly Father’s family was never intended to be confined to Israel and to consist of only the Jews.

The Kingdom of Heaven imposes demands on the personal commitment of the disciple, which must often supersede natural family ties and even ethnic bonds. Our Lord’s reply indicates that he regards his mother to be more of a mother to him by being a woman of faith, without which she could never have become his natural mother in the hypostatic order of his incarnation, nor thereby the mother of all his disciples in the spiritual family of God. Mary herself is as much a disciple of her Son as John and the other apostles are, and by being a fellow disciple (the first and foremost), she can be their spiritual mother to lead them in corroboration with her mystical spouse, the Holy Spirit in their great commission after her Son’s ascension.

These two verses, therefore, introduce the image of a new family that takes on an eschatological aspect and rises above the national bond that connects the group of listeners encircling Jesus. These passages are a prelude to our Lord’s intentions when he addresses his mother and the disciple from the Cross. There, he uses the same hinneh clause to underscore how his mother, Mary, is truly a mother in the economy of salvation so that there should be no misunderstanding. It is not that she shall be like a mother to the Disciple, but instead, she will be his actual mother from then on in the Kingdom of Heaven, as he shall be her son as much as Jesus is physically, though in a spiritual way. The Church is our mother, as Mary is a mother to us, but only in an allegorical sense. Our Blessed Lady is our personal mother, having conceived and given birth to Jesus, our Lord and brother (Rom 8:29).

In establishing this family of faith during his active ministry, Jesus began redefining Israel as Mother Zion's figure with his mother, Mary, in mind. The nation shall no longer be defined by national boundaries or birthright but by faith, as the New Zion or Church shall extend beyond its borders and receive the Gentiles into God’s family kingdom. This vision of Zion goes beyond the metaphorical. It reaches its secondary fulfillment in the Blessed Virgin Mary, Our Lady of Sorrows, and Mother of the Church, in which all the faithful may relate to their mother on a personal level, as much as they do relate with their Lord and brother, her resurrected divine Son, in filial prayer and devotion, as members of His Mystical Body.

“For if Mary, as those declare who with

sound mind extol her, had no other son but

Jesus, and yet Jesus says to His

mother, Woman, behold thy son,’ and not Behold

you have this son also,’ then He

virtually said to her, Lo, this is Jesus, whom thou

didst bear.’ Is it not the

case that everyone who is perfect lives himself no longer, but

Christ lives in

him; and if Christ lives in him, then it is said of him to Mary, Behold thy

son

Christ.’”

Origen, Commentary on John, I:6 (A.D. 232)

So, the ransomed of the LORD shall

return,

and come to Zion with singing;

everlasting joy shall be upon their heads;

they shall obtain joy and gladness,

and sorrow and sighing shall flee away.

Isaiah 51,11

.webp)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.webp)

.png)

.png)

.webp)

.png)